P15: Whatever is, is in God/Nature, and nothing can be or be conceived without God/Nature.

Dem.: Except for God/Nature, there neither is, nor can be conceived, any substance (by P14), i.e. (by D3), thing that is in itself and is conceived through itself. But modes (by D5) can neither be nor be conceived without substance. So they can be in the Divine/Universal nature alone, and can be conceived through it alone. But except for substances and modes there is nothing (by A1). Therefore, {everything is in God/Nature and} nothing can be or be conceived without God/Nature, q.e.d.

Schol.: [I.] There are those who feign a God/Nature, like man, consisting of a body and a mind, and subject to passions. But how far they wander from the true knowledge of God/Nature, is sufficiently established by what has already been demonstrated. Them I dismiss. For everyone who has to any extent contemplated the Divine/Universal nature denies that God/Nature is corporeal. They prove this best from the fact that by body we understand any quantity, with length, breadth, and depth, limited by some certain figure. Nothing more absurd than this can be said of God/Nature, viz. of a being absolutely infinite.

But meanwhile, by the other arguments by which they strive to demonstrate this same conclusion they clearly show that they entirely remove corporeal, or extended, substance itself from the Divine/Universal nature. And they maintain that it has been created by God/Nature. But by what Divine/Universal power could it be created? They are completely ignorant of that. And this shows clearly that they do not understand what they themselves say.

At any rate, I have demonstrated clearly enough—in my judgment, at least—that no substance can be produced or created by any other (see P6 C and P8 S2 C). Next, we have shown (P14) that except for God/Nature, no substance can either be or be conceived, and hence {in P14 C2} we have concluded that extended substance is one of God/Nature’s infinite attributes. But to provide a fuller explanation, I shall refute my opponents’ arguments, which all reduce to these.

[II.] First, they think that corporeal substance, insofar as it is substance, consists of parts. And therefore they deny that it can be infinite, and consequently, that it can pertain to God/Nature. They explain this by many examples, of which I shall mention one or two.

[i] If corporeal substance is infinite, they say, let us conceive it to be divided in two parts. Each part will be either finite or infinite. If the former, then an infinite is composed of two finite parts, which is absurd. If the latter {i.e., if each part is infinite}, then there is one infinite twice as large as another, which is also absurd.

[ii] Again, if an infinite quantity is measured by parts {each} equal to a foot, it will consist of infinitely many such parts, as it will also, if it is measured by parts {each} equal to an inch. And therefore, one infinite number will be twelve times greater than another {which is no less absurd}.

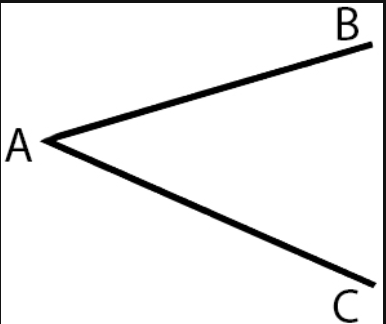

[iii] Finally, if we conceive that from one point of a certain infinite quantity two lines, say AB and AC, are extended to infinity, it is certain that, although in the beginning they are a certain, determinate distance apart, the distance between B and C is continuously increased, and at last, from being determinate, it will become indeterminable. Since these absurdities follow—so they think—from the fact that an infinite quantity is supposed, they infer that corporeal substance must be finite, and consequently cannot pertain to God/Nature’s essence.

[III.] Their second argument is also drawn from God/Nature’s supreme perfection. For God/Nature, they say, since he is a supremely perfect being, cannot be acted on. But corporeal substance, since it is divisible, can be acted on. It follows, therefore, that it does not pertain to God/Nature’s essence.

[IV.] These are the arguments which I find authors using, to try to show that corporeal substance is unworthy of the Divine/Universal nature, and cannot pertain to it. But anyone who is properly attentive will find that I have already replied to them, since these arguments are founded only on their supposition that corporeal substance is composed of parts, which I have already (P12 and P13 CP13C) shown to be absurd. And then anyone who wishes to consider the matter rightly will see that all those absurdities (if indeed they are all absurd, which I am not now disputing), from which they wish to infer that extended substance is finite, do not follow at all from the fact that an infinite quantity is supposed, but from the fact that they suppose an infinite quantity to be measurable and composed of finite parts. So from the absurdities which follow from that they can infer only that infinite quantity is not measurable, and that it is not composed of finite parts. This is the same thing we have already demonstrated above (P12, etc.). So the weapon they aim at us, they really turn against themselves.

If, therefore, they still wish to infer from this absurdity of theirs that extended substance must be finite, they are indeed doing nothing more than if someone feigned that a circle has the properties of a square, and inferred from that the circle has no center, from which all lines drawn to the circumference are equal. For corporeal substance, which cannot be conceived except as infinite, unique, and indivisible (see P8, P5 and P12), they conceive to be composed of finite parts, to be many, and to be divisible, in order to infer that it is finite.

So also others, after they feign that a line is composed of points, know how to invent many arguments, by which they show that a line cannot be divided to infinity. And indeed it is no less absurd to assert that corporeal substance is composed of bodies, or parts, than that a body is composed of surfaces, the surfaces of lines, and the lines, finally, of points.

All those who know that clear reason is infallible must confess this—particularly those who deny that there is a vacuum. For if corporeal substance could be so divided that its parts were really distinct, why, then, could one part not be annihilated, the rest remaining connected with one another as before? And why must they all be so fitted together that there is no vacuum? Truly, of things which are really distinct from one another, one can be, and remain in its condition, without the other. Since, therefore, there is no vacuum in nature (a subject I discuss elsewhere), but all its parts must so concur that there is no vacuum, it follows also that they cannot be really distinguished, i.e., that corporeal substance, insofar as it is a substance, cannot be divided.

[V.] If someone should now ask why we are, by nature, so inclined to divide quantity, I shall answer that we conceive quantity in two ways: abstractly, or superficially, as we {commonly} imagine it, or as substance, which is done by the intellect alone {without the help of the imagination}. So if we attend to quantity as it is in the imagination, which we do often and more easily, it will be found to be finite, divisible, and composed of parts; but if we attend to it as it is in the intellect, and conceive it insofar as it is a substance, which happens {seldom and} with great difficulty, then (as we have already sufficiently demonstrated) it will be found to be infinite, unique, and indivisible.

This will be sufficiently plain to everyone who knows how to distinguish between the intellect and the imagination—particularly if it is also noted that matter is everywhere the same, and that parts are distinguished in it only insofar as we conceive matter to be affected in different ways, so that its parts are distinguished only modally, but not really.

For example, we conceive that water is divided and its parts separated from one another—insofar as it is water, but not insofar as it is corporeal substance. For insofar as it is substance, it is neither separated nor divided. Again, water, insofar as it is water, is generated and corrupted, but insofar as it is substance, it is neither generated nor corrupted.

[VI.] And with this I think I have replied to the second argument also, since it is based on the supposition that matter, insofar as it is substance, is divisible, and composed of parts. Even if this {reply} were not {sufficient}, I do not know why {divisibility} would be unworthy of the Divine/Universal nature. For (by P14) apart from God/Nature there can be no substance by which {the Divine/Universal nature} would be acted on. All things, I say, are in God/Nature, and all things that happen, happen only through the laws of God/Nature’s infinite nature and follow (as I shall show) from the necessity of his essence. So it cannot be said in any way that God/Nature is acted on by another, or that extended substance is unworthy of the Divine/Universal nature, even if it is supposed to be divisible, so long as it is granted to be eternal and infinite. But enough of this for the present.